I’ve been a bit quiet on the Blog front for a few months… and some of those based in the Joseph Banks Laboratories may have noticed that my chair has also being empty for some time. I want to talk about something that many people, including myself, often have real issues discussing – mental health. Until we can discuss mental health in the same way we can any other disease or illness it shall remain a problem. I want to try and be as open as I can about this, and try to share both the difficulties I have experienced and the solutions I have found so that other graduate students who are either currently experiencing or have previously experienced these feelings, will not feel as isolated. Rather than solely preach my own advice, I have also asked other veterans of Grad School (both at Lincoln and at other institutions worldwide) to share there own experiences and advice.

Physical Illness

Mental Illness

Firstly, you are not alone:

During my undergraduate years and probably through to my 2nd Year of my Ph.D., I viewed academics as stoics that were the masters of their minds and are able to battle all stressors related to their work. Manuscript submission? No problem! Conference presentation? Easy! Grant proposals? Done! Although some supervisors might disagree, academics are not immortal gods, nor Superheroes immune to human emotions. The stressors that apply to Ph.D. students still apply to them, although the amplitude of this anxiety may be more controlled through years of experience.

I started googling “Mental Health in Academia” in the hope of inspiration and re-assurance that I wasn’t alone. Expecting one or two success stories of scientists overcoming their mental health disorders to ‘make-it’ in academia, I was astounded by just how rampant depression and anxiety is in academia. A recent Australian study found that the rate of mental illness in academia was three to four times higher than in the general population; and (in one of the very few studies conducted in this field) that up to 53% of academics in the UK suffer from mental illness (Kinman, 2010). There is an on-going argument akin to the classic “Nature vs Nurture” debate in biology as to why there is a higher rate of mental distress in academia than in the other careers; questioning if a career in academia has a detrimental impact on our mental health, or if an academic lifestyle attracts those more susceptible to mental health disorders.

To paraphrase the famous quote “Look at the academic to your left, look at the academic to your right – it is likely that one of the two has experienced mental distress”.

For the new breed…

I hope this is not too much of a broad generalisation, but chances are if you made it to graduate school you did well at college and undergraduate level. At these institutes, your work would have been graded and you would have known exactly where you stand against your previous work and the work of others. You would continually assess how you measure up to your peers. This doesn’t work at post-graduate level for the simple reason that no two people are working on exactly the same assignment.

You would also be used to submitting a piece of work, have it graded, and then never look at it again. This too is a thing of the past in graduate school. Work WILL be handed back to you plastered in corrections, and it will most likely be soul destroying. Please please understand, this is not a reflection on your ability to create great work, this is just part of the process in graduate school, the continual polishing of a piece of work.

You will (and I can pretty much guarantee this) see how much work your peers have done, or how well their experiments are going and feel to some extent that you are failing or not good enough to do an MSc/PhD.; a thought process that often leads to “Impostor syndrome” (feeling like an impostor that has almost mistakenly been accepted into graduate school that are not smart enough to complete their course). Any seasoned member of Grad School knows and understands the dismay that the impostor syndrome can cause. I was recently at the Nature Careers Expo in London where there was a Q&A about life in academia, with questions directed to a panel of renowned scientists. One student rose her hand and expressed her difficulties accepting that she was good enough to complete her Ph.D., and asked the panel at what point their feelings of being an impostor dissipated. A Professor from Oxford immediately stated “It hasn’t”, followed by a chorus of nods from the rest of the panel. The intention of this previous point is not to frighten readers that impostor syndrome is incurable, but rather that your scientific idols likely experience the same thoughts and fears as you.

My final point to the newcomers, take time off for yourself! In my fist year of my Ph.D. I worked ridiculous hours. 7am-10pm Monday – Saturday, with a half day on Sunday. Did I have to? No, but I felt like I needed to impress everyone and prove my worth. However, working with this level of intensity is counter-productive as you will make mistakes (admittedly, sometimes expensive ones!). Burning out is a real issue that all grad students deal with at some point, where they feel guilty for taking time off for themselves, despite their body and mind screaming for a break. Graduate school truly is a marathon, not a sprint. It takes time to find your pace at which you are most efficient (I personally still struggle with this), however sprinting to the point of exhaustion is not the answer.

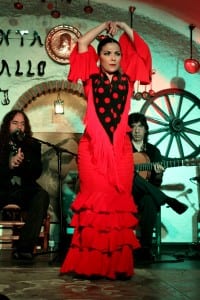

A trip to a science museum (or for me, as a Marine Biologist, going rockpooling) is a great compromise to the struggle between work and play; allowing your brain to slow while keeping the “I should be working” demons at bay.

Grad Students to the Rescue!

I’ve asked a number of graduate students and academics from around the world (God Bless Reddit!!) what advice they would give to graduate students who are experiencing mental distress in the workplace. Below are some of the gems of knowledge I’ve received.

“This is where effective time management skills will shine, especially if some days are worse for you than others. Second, identify an activity you enjoy doing and be sure and always make time for that thing no matter what.”

“My biggest surprise was how common it is for graduate students to be affected by anxiety and depression. I finally had a candid conversation with fellow students, and we were ALL on some kind of anti-depressant or anti-anxiety medication. I believe there were five of us talking about it. I was shocked. And I felt so relieved because it made me feel “normal.” “

“Don’t be afraid to use your school’s mental health services. A lot of people in the outside world would kill to have access to free counselling and psychiatry. Your school wants you to succeed so they’re there to help!”

“After an incredibly rough first year as a doc student – the only one in my cohort with no research experience – discovering Impostor Syndrome was a lifesaver (probably not literally but I was pretty depressed so who knows). The vast majority of academics are all dealing with the same anxieties, doubts, etc.”

“Remember, that you are not a fully fledged scientist. You are training to be a scientist. Things will go wrong, break, and not work out – just remember you are still learning!”

“Talk to your supervisor/PI if you are struggling, or at least one of the Post-Docs. Its likely they have either dealt with anxiety/depression, or helped those with it. You are not the first, and won’t be the last to ask for help”

“If you’re comfortable with them, be open with your advisor about things your going through and what you know helps you or ways they can support you. They might have gone through some difficult times themselves when they were students.

I’ve witnessed some really awesome advisors be there for their student, advocating for them and being their biggest supporter. But they can’t help you if they don’t know your situation.

Having anxiety and being depressed is still stigmatized, but the only way we’re going to change that is if we take steps to help each other and make a more accepting work environment”

“I think this is actually a pretty big issue that people don’t talk about. I’m glad you hear you’re trying to start a conversation about it. Ultimately I think there are certain things about the culture of graduate school that amplify insecurities and anxieties. It’s important that we try to change them, but in the short term it’s important just to recognize it and remove the stigma surrounding mental health disorders.”

I hope someone out there has gained some comfort from this post. If you have any advice you wish to share, I am happy to add it to this post. If anyone is struggling out there and wants to talk, or just fancies a coffee and a chat about the world – please feel free to email me: jsage@lincoln.ac.uk

You can do this 🙂